Introduction

Microsoft states that “the forest (not the domain) is the security boundary in an Active Directory implementation”, meaning that Domain Admins of a child domain is essentially as privileged as Enterprise Admins in a root domain and will have administrative rights in all domains of the forest. Why? We guessed that the default trust between domains inside a forest enables any child domain to trick the root domain to treat child domain users as Enterprise Admins by abusing the SID history (ExtraSids) functionality – this attack/technique is known as “Access Token Manipulation: SID-History Injection” and is explained in a later part of this series.

In default AD configuration SID-History injection is possible inside a forest, but in theory, it can be prevented with SID filtering which is enabled by default between forests, according to Microsoft “SID filtering helps prevent malicious users with administrative credentials in a trusted forest from taking control of a trusting forest”.

This poses the question – can we use SID filtering to make the domain a security boundary?

We have researched this question; our work is published in this series of seven blog posts which can be read independently from the context of our specific topic.

Kerberos authentication explained

In part 1, we explain everything you need to know about the underlying Kerberos authentication mechanisms to understand the attacks, defenses, and research in the rest of the series.

Part 2 reviews known methods of escalating from a child domain to a parent domain

Part 3 describes known methods for preventing attacks using SID filtering.

Part 4-7 describe our research findings and novel trust attacks.

We started with a structured research methodology, where we examined the SIDs allowed to pass through SID filtering and iterating through all AD objects in a parent domain to identify permissions for the given SIDs that potentially could be exploited. But as with all great science – the best results were found by coincidence.

Big thanks to harmj0y, Cyb3rWard0g, Dirk-jan, XPN, gentilkiwi, YuG0rd, and PyroTek3 for great tools and inspiring blogposts about Kerberos and AD security.

Content

Introduction

Background knowledge

SID structure

SID history

AD group scopes

Basic Kerberos authentication

AS Exchange

TGS Exchange

AP Exchange

Golden and silver tickets

Cnconstrained delegation

AD Trust

Kerberos authentication to a parent domain

AS Exchange

TGS Exchange (child KDC)

TGS Exchange (parent KDC)

AP Exchange

Preliminary conclusion

Background knowledge

To get a proper understanding of the attack methods, we need to understand how Kerberos and AD work together in specific areas. The following sub-sections should provide the knowledge necessary to understand why the attacks methods are possible.

SID structure

The SID (Security Identifier) is a unique ID that all security principals (users, computers, groups, service accounts) have in Windows environments.

The test user in our AD lab has the SID:

S-1-5-21-4020112180-1664985325-2996139612-1103

The bold part is the SID of the domain to which the user belongs. The SIDs of all domain security principals begin with the domain SID. The italic part is the RID (Relative Identifier) and is unique for every security principal in the same domain.

Well-known security principals like the Domain Admins group exist in every domain and have the same RID. For example, the Domain Admins group of a child and root domain has the same RID.

SIDs of built-in Windows groups, which exist by default on all Windows computers no matter if the computer is domain-joined or not, all are prefixed with S-1-5-32. For example, Administrators have the SID S-1-5-32-544 on all Windows computers.

For a more thorough description of SID, read this Microsoft article.

SID history

When migrating AD security principals (e.g., users and groups) from an old domain to a new one, principals will get a new SID in the new domain and lose their old SID. Because permissions in AD are granted to a principal’s SID, migrated principals will lose their access to resources in the old domain. The security principal attribute SID-History is therefore used to let principals keep their access even when migrated. The attribute holds the security principal's SID from the previous domains the security principal belonged to.

AD group scopes

There are three scopes of AD groups:

· Domain local

· Global

· Universal

Additionally, the built-in groups in the Builtin AD container have a special scope called builtin local.

The main difference between the scopes is which security identifiers are allowed to be a member of the groups, and where the groups can have permissions. E.g. a global group is only allowed to have members of the same domain as the global group itself, whereas universal and domain local groups can have users from the entire forest as a member. In terms of permissions for example, domain local groups can only have permissions on AD objects of their own domain.

All the rules are not important for this topic, you just need to know that these scopes exist and there are rules for in which context a group can be used based on its scope.

An example of a global group that exists by default is Domain Admins. It exists in every AD domain, where Enterprise Admins is a universal group and only exists in the root domain of the AD forest.

A full Microsoft description of AD group scopes can be found here.

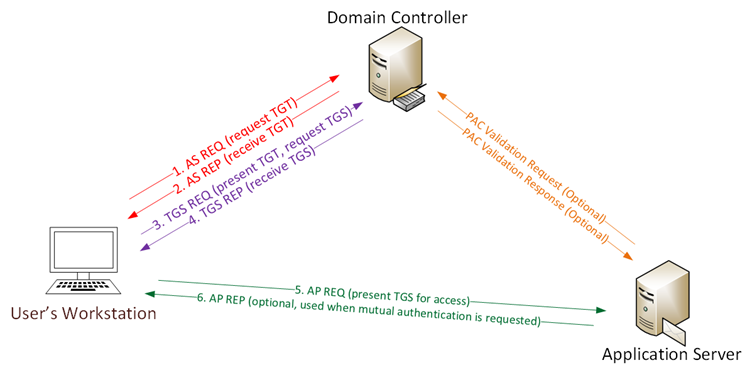

Basic Kerberos authentication

In a nutshell, Kerberos (/ˈkɜːrbərɒs/) is a computer network authentication protocol that works on the basis of tickets and enables nodes communicating over a non-secure network to prove their identity to one another in a secure manner. According to Wikipedia the AD implementation of the Kerberos v5 authentication protocol (RFC4120) is called MS-KILE. When we mention Kerberos, we refer to MS-KILE.

The standard Kerberos authentication is between a client user (a security principal in AD) and a Domain Controller (DC). The service responsible for the Kerberos authentication on a DC is called the Key Distribution Center (KDC). The KDC consists of the Authentication Service (AS) and the Ticket Granting Service (TGS). When authenticated, the client user can communicate with an application server via the Authentication Protocol (AP). The abbreviations of the three services names are reflected in the prefix of the authentication messages going to and from the services:

The ‘TGS’ in ‘request TGS’, ‘receive TGS’, and ‘present TGS’ is the service ticket in the figure. To use TGS as an abbreviation for ‘service ticket’ is a widespread choice, despite it is the acronym for Ticket Granting Service and therefore misleading. Image borrowed from: https://adsecurity.org/?p=1515.

The basic flow is:

AS-REQ: User requests a session ticket

AS-REP: User receives a session ticket

TGS-REQ: User requests a ticket for a given service, by presenting their session ticket

TGS-REP: User receives a service ticket

AP-REQ: User requests access to the service, by presenting their service ticket

AP-REP: User receives permission to access the service

AS Exchange

In short: The AS Exchange is the client authentication where the client user requests a session ticket called a Ticket-Granting Ticket (TGT) with an AS-REQ message and gets an AS-REP reply from the KDC containing the TGT. The TGT is later used to prove that the client user is authenticated when the client user requests a ticket to a given service.

In full: The AS-REQ is a message with the principal name of the client user, pre-authentication data encrypted with the client user’s secret key (aka. Kerberos user key, encryption key, Kerberos hash, etc.), and more data we will not focus on. The user’s secret key is an encryption key derived from the password of the client user. The secret keys of all domain users are stored in the NTDS database on the DCs and are generated on the client-side when the user types in their password. Kerberos supports the following encryption key types, with the weakest algorithm listed first:

DES-CBC-CRC

DES-CBC-MD5

RC4-HMAC-EXP

RC4-HMAC

AES128-CTS-HMAC-SHA1-96

AES256-CTS-HMAC-SHA1-96

DES is not accepted by the KDC by default due to the weakness of the algorithm. An RC4-HMAC key is identical to a Windows NT key (NT password hash), which is used for NTLM authentication. RC4-HMAC-EXP is the same as RC4-HMAC but with a reduced key length, but it is not clear when it can be used. The AES algorithms use a cryptographic salt with the username and the domain name.

The Kerberos encryption key type used depends on what is supported by the client user, the client computer OS, the KDC, the service account, and more. Different encryption key types are often throughout the authentication process. For example, the service ticket cannot be encrypted with AES if the service account does not support AES, but that does not prevent the TGT from being encrypted with AES. You can read more about the supported encryption key types and how to configure them here.

AS-REQ

When the human being at the keyboard has typed in their password, the client user (client computer) will generate the user’s secret key for each of the encryption types supported by the computer. The client user encrypts the pre-authentication data with the strongest secret key available. The name of the Kerberos encryption type used for encrypting the pre-authentication data is included together with a list of all the types supported by the computer in the AS-REQ.

The ‘System Key’ (computer Kerberos credentials) is used prior to the Kerberos user authentication and is therefore included in official Microsoft figures.

The KDC uses the principal name to look up the secret key for the client user in the NTDS database and uses this key to decrypt and verify the pre-authentication data. The pre-authentication data for a normal password logon is a simple timestamp (PA-ENC-TIMESTAMP). If the timestamp is less than 5 minutes old (specified limit by the default maximum tolerance for computer clock synchronization), the timestamp is valid and client user identity is thereby proven to the KDC. The pre-authentication is different for other types of logons e.g., smart card, but we will not dig into that.

AS-REP

When the KDC has verified the identity of the client user, the KDC will respond with an AS-REP message.

The AS-REP contains three main parts:

Ticket information, metadata including for how long the Kerberos session is valid.

TGS (Ticket-Granting Service) session key, a key that the client user must use to encrypt the TGS-REQ message later in the TGS Exchange. Both the ticket information and the TGS session key are encrypted with the user’s secret key.

TGT (Ticket-Granting Ticket), a Kerberos session ticket that proves the client user has been authenticated. It contains a copy of the TGS session key and the User Credentials, aka. the PAC (Privilege Attribute Certificate). The PAC is a data structure consisting of group membership, profile and policy information, and other credential information about the client user.

The PAC is included in the TGT unless the client user explicitly requests the PAC be excluded from the ticket in the AS-REQ request. In its bare form, the Kerberos v5 protocol (RFC4120) only provides authentication (i.e. who you are), PAC (MS-PAC) is a Microsoft addition that adds authorization (i.e. what you are allowed to do).

The TGT is encrypted with the secret key of a special built-in AD user named krbtgt. In the figures above, the krbtgt secret key is outlined in yellow and called the Ticket-Granting Service Key. Technically, the TGT allows for cracking the krbtgt secret key, but it is not feasible as the password of krbtgt is a long random string set by DC.

Disabled Pre-authentication

It is possible to allow client users to skip the pre-authentication part of AS-REQ by setting the DONT_REQ_PREAUTH property flag on the AD user object, which makes the client user vulnerable to AS-REP Roasting. Attackers then only need to send the principal name of a target client user in an AS-REP message to receive an AS-REQ message including the TGS session key encrypted with the targeted client user’s secret key. The encrypted TGS session key can be cracked offline to obtain the client user’s password. Fortunately, Kerberos v5 protocol (RFC4120) came with optional pre-authentication which prevents this attack. Pre-authentication is enabled by default in MS-KILE.

TGS Exchange

TGS-REQ

When a client user wants to access a service, the client user will send the Service Principal Name (SPN) of the service along with the client user’s TGT and an authenticator in a TGS-REQ message to the KDC. The authenticator contains the client user’s name and a timestamp that proves the validity of the Kerberos session and is encrypted with the TGS session key

The KDC decrypts the TGT to get the TGS session key and then decrypts the authenticator.

The KDC checks if the data of the authenticator is accurate (again decided by the default maximum tolerance for computer clock synchronization), and if valid, the user is authenticated.

TGS-REP

The KDC does not check whether the client user has the necessary rights to access the requested service but will include a copy of the PAC from the TGT in a service ticket and send the service ticket to the client user in the TGS-REP message.

The service ticket is encrypted with the service key, which is the secret key of the service account. An AP session key for the AP Exchange is included in the TGS-REP (called Session Key in the figures), encrypted with the TGS session key in the TGS-REP. The AP session key is also included inside the service ticket.

AP Exchange

AP-REQ

The client user forwards the service ticket to the service account in the AP-REQ message, together with an authenticator encrypted with the AP session key.

The service account decrypts the service ticket using the service key (its own secret key). The content of the PAC from the service ticket is read and used to determine whether the client user has the necessary privileges to access the requested service. The service can be configured to perform the optional PAC validation, where it sends the PAC to the DC to validate the PAC’s content by checking the checksum of the PAC. This feature is disabled by default.

The AP session key is retrieved from the service ticket by the service account. The AP session key is used to decrypt the authenticator which contains the client user’s name and a timestamp that proves the validity of the Kerberos session.

AP-REP

If the client user has requested mutual authentication (default with the MutualAuthentication boolean in the AP-REQ), the service account will respond with an AP-REP containing a timestamp encrypted with the AP session key.

The client user decrypts the timestamp using its own copy of the AP session key and verifies the identity of the service account.

Golden and silver tickets

Basic Kerberos authentication has two types of tickets:

The TGT encrypted with the secret key of krbtgt

The service ticket encrypted with the secret key of the service account

The KDC can create these tickets, as the KDC has access to the secret keys of all AD accounts stored on the DC. But, if an attacker gets hold of the secret key (or password) of either krbtgt or a service account, the attacker can create its own forged TGTs or service tickets, respectively, as the remaining data required to create these tickets are available to all AD users.

Golden ticket: Forged TGT

Silver ticket: Forged service ticket

The krbtgt secret key is only obtainable with administrative rights on a DC i.e., Domain Admins membership, or with DCSync permission on the krbtgt account. A service account’s secret key or password can be retrieved from not only the DC, e.g. the memory of computers where the service account runs its service, or from Kerberoasting.

The cool thing about golden and silver tickets is that the creator of the ticket decides what data the tickets should contain, and this data will be treated as valid. A TGT is by default valid for a 10 hour period and can be extended for a max of 7 days. But an attacker can specify the ticket to be valid for up to 10 years.

If the krbtgt secret key is correct, the KDC will accept a forged validation period, despite the policy for creating TGTs on DCs stating that TGTs should only be valid for only 10 hours.

Neither the secret key nor password of the user which the golden ticket represents is required in order to create or use a golden ticket. The TGS-REQ only requires the client user to send a TGT and an authenticator encrypted with the TGS session key. As the TGS session key is not stored on the DC but inside the TGT and extracted from the TGT by the KDC when the KDC receives the TGT, the attacker can create their own TGS session key and put that into the TGT and use it for encrypting the authenticator. In other words, the client user’s secret key is not required when creating a forged TGT, and resetting the password of the user does not make the golden ticket invalid. Attackers can even create golden tickets as disabled, deleted, or non-existing users since the user will not be verified by the KDC - that is, if the TGT is less than 20 min old.

A golden ticket can be made invalid by changing the krbtgt password twice. The password change results in new secret keys for krbtgt, but it must be done twice as the first secret key in the password history of the account is valid as well (Microsoft states that the password history of krbtgt is two, which could mean it should be reset thrice, but this is not the case). You must wait until all DCs has replicated the new krbtgt secret keys around before the second reset to prevent making legitimate TGTs invalid.

The silver ticket follows the same principles as the golden ticket, except the silver ticket is a limited ticket valid for only the given service instead of a TGT. A silver ticket with a forged PAC can be blocked if PAC validation is performed during the AP Exchange, which is unfortunately not the default case due to performance overhead.

Unconstrained delegation

When users access a front-end service that accesses a back-end service, we have a problem with Kerberos known as the Kerberos double-hop issue. A service knows what permissions a user has by the information in the service ticket, but how should the back-end service know what access a user has when access happens through a front-end service?

Image borrowed from: https://adsecurity.org/?p=1667

Microsoft solved this issue in Windows 2000 version of AD with unconstrained delegation. The front-end service account will have its UAC property populated with the flag TRUSTED_FOR_DELEGATION, which means this account is set up for unconstrained delegation. When users request a service ticket to the front-end service, the KDC will add the client user’s TGT into the service ticket, such that the front-end service account can impersonate the client user, by requesting service tickets to the back-end service as the client user.

Microsoft later introduced the more secure constrained delegation as an alternative, and latest the improved resource-based constrained delegation. These will not be covered in this blogpost as only unconstrained delegation will be exploited as part of this series.

AD Trust

Trust relations are defined between domains and forests to enable Kerberos authentication for resource access across domains. A child domain will have a two-way trust relation with the parent domain by default. The parent-child trust is transitive, meaning if A trusts B, and B trusts C, then A will trust C. Therefore, all domains within a forest trust each other by default. Domains in separate forests will not trust each other by default.

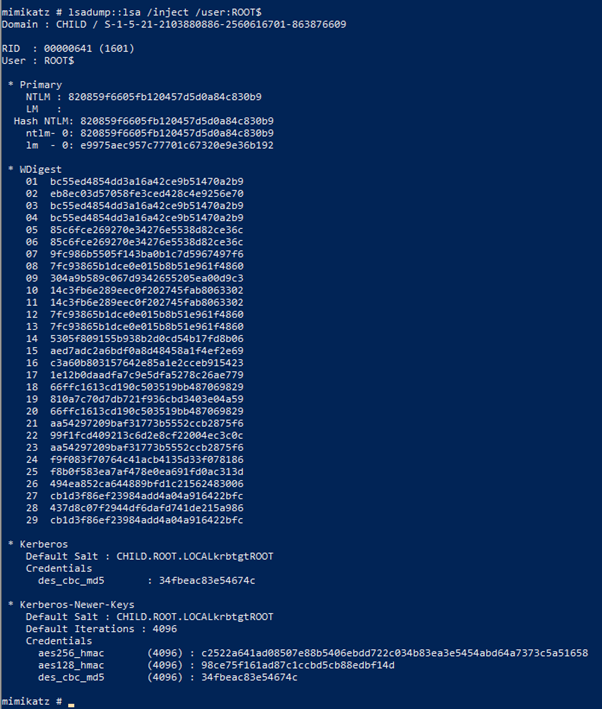

When a two-way trust is created, a user account is created in each domain where the username is set to the NetBIOS domain name of the other domain followed by $, e.g. CHILD$ created in the ROOT domain, and ROOT$ created in the CHILD domain. The same password is set on both accounts, resulting in identical Windows NT hashes and Kerberos RC4 secret keys for the two accounts. The Kerberos AES secret keys are not identical as these keys are generated with a cryptographic salt containing the domain and username, which are different for the two accounts. Here is an example of such two users dumped with Mimikatz:

Notice how the Windows NT hashes (NTLM in Mimikatz terms) are identical but the Kerberos AES keys are different due to the different salts used.

The trust account’s passwords are used as shared secrets between the domains, and the trust account’s Kerberos secret keys derived from the passwords are used as inter-realm trust keys, which are the keys used for encryption of Kerberos tickets between the domains. The Kerberos (RFC4120) term “realm” is the equivalent of “domain” in the world of AD. The AES secret keys of the trust accounts are not identical to the AES inter-realm trust keys, as a different cryptographic salt is used.

Mimikatz can dump all the inter-realm trust keys:

Notice how the rc4_hmac_nt values are identical to the Windows NT hash of the two accounts CHILD$ and ROOT$.

This setup enables the TGS in a domain, to treat the TGS of another domain, almost as just another service when a client user requests access to service in another domain.

All four trust keys are identical when the trust is created but changed to unique values after 30 days. Here we see that change from in the ROOT domain:

And here the change in the CHILD domain:

The output gives us four sets of inter-realm trust keys, derived from the current and previous passwords of the trust accounts. In the last screenshot, the [ In ] and [ In-1 ] entries are the current password and the previous password for ROOT$ where [ Out ] and [ Out-1 ] are the current password and the previous password for CHILD$. This is the opposite when the keys are dumped from in the ROOT domain. The inter-realm trust keys derived from ROOT$’s password are used for encrypting a Kerberos ticket (inter-realm TGT, explained in the next section) when a CHILD domain user access a ROOT service, the inter-realm trust keys derived from CHILD$’s password are used when a ROOT domain user access a service in the CHILD domain.

The inter-realm trust keys derived from the previous passwords of the trust accounts are supported as well as the ones derived from the current password. This is to make sure legitimate tickets are not invalidated when the password of a trust account is changed, just like with the krbtgt account and TGTs.

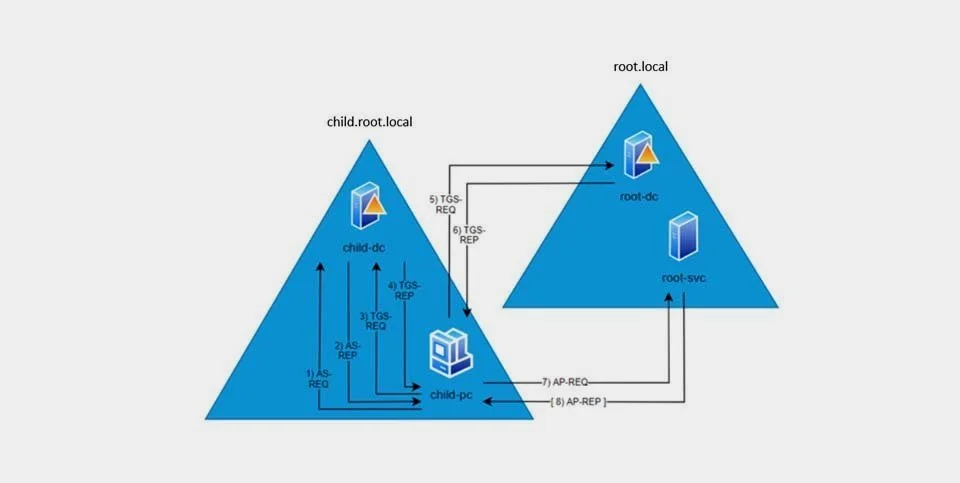

Kerberos authentication to a parent domain

A DC holds only the Kerberos secret keys of the AD accounts of the domain the DC belongs to. So, when a user asks for access to a service outside of the domain, the KDC cannot access the secret key of the service account in the other domain and thereby can’t create an encrypted service ticket. However, it is possible to get access to services in other domains if there is trust between the domains.

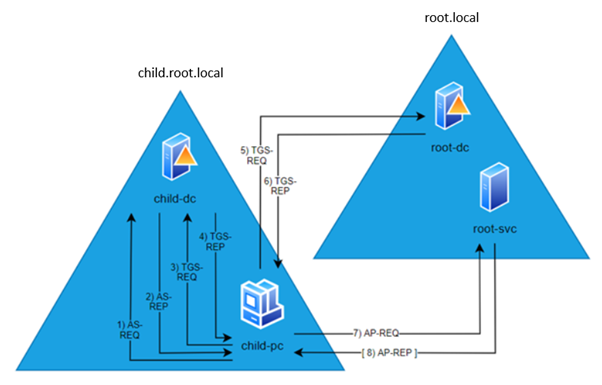

The next figure illustrates Kerberos authentication from the client user is authenticated in its own domain to the client user has gained access to the service in the parent domain.

Notice how the steps are the same as Kerberos authentication inside a single domain, except TGS Exchange with the parent KDCc has been added. Yet another TGS Exchange would be added if the authentication was to a service of a third domain with a trust relationship with the parent domain e.g. a sibling domain to the child.

We will in this section not dive into the details already covered in the Basic Kerberos authentication section but look closer at the content of the Kerberos tickets and explain when things are different from Kerberos authentication inside a single domain.

It is not completely clear in the Microsoft documentation of MS-KILE, MS-PAC, etc when group SIDs and SID history are added to the PAC and to which attributes throughout the authentication phases. So, we have tested in our own AD lab. It is possible to decrypt Kerberos tickets using decryptKerbTicket.py by xan7r. Domain Admins privileges the encryption keys (krbtgt secret key, trust key, service account secret key) can be obtained using Mimikatz. The tickets can also be extracted from memory with Mimikatz.

AS Exchange

The AS Exchange before a client user requests access to a service in a parent domain is identical to the AS Exchange of a normal Kerberos authentication where the client user requests access to service inside the domain.

1) AS-REQ

The client user requests a TGT. The AS-REQ includes pre-authentication data encrypted with the client user’s secret key, which proves its identity to the KDC.

2) AS-REP

The KDC responds with a TGT. The list below is a selection of PAC attributes of the TGT PAC:

LogonDomainId: SID of client user domain

UserId: RID of client user

PrimaryGroupId: RID of client user’s primary group

In our test, the value was 513 representing the group Domain Users.

UserFlags: Integer

UserFlags is an integer containing bit flags describing the user logon and other stuff. The value was 32 in our test, meaning the flag ‘D’ is set: “Indicates that the ExtraSids field is populated and contains additional SIDs”.

GroupIds: List of group RIDs

The list contains the RIDs of global and universal groups of the client user domain of which the client user is a member. The list contains only the RIDs and not the SIDs, as all the groups begin with domain SID which is in the LogonDomainId attribute. This makes the PAC smaller in bytes. Note that domain local groups are not in this list. More on that when we get to the service ticket.

ExtraSids: List of extra SIDs

ExtraSids contains SIDs of groups/identities of the client user which does not begin with the domain SID. That is:

SIDs of universal groups of other domains

SID history SIDs

Other identities (e.g. S-1-18-1 Authentication authority asserted identity)

The SID S-1-18-1 is mandatory. It means the client's identity is asserted by an authentication authority based on proof of possession of client credentials. It was introduced in Windows 8 / Server 2012.

SidCount: Number of SIDs in ExtraSids

ResourceGroupDomainSid: NULL

ResourceGroupIds: NULL

ResourceGroupCount: 0

TGS Exchange (child KDC)

3) TGS-REQ

A client user wants to access a service in the parent domain and sends a TGS-REQ to the TGS of the child domain. Since the domain name of the service is different from the child domain name, the client user will include the option NAME_CANONICALIZE in the TGS-REQ to indicate the service may be in another domain.

4) TGS-REP

The TGS realizes that the service is in another domain by the service name, and sends back a TGS-REP of the type TGS referral containing:

Pre-authentication data

The Pre-authentication type PA-SVR-REFERRAL-INFO indicates the message is a referral. Where the normal PA-ENC-TIMESTAMP pre-authentication contains the client user’s name and a timestamp, PA-SVR-REFERRAL-INFO contains the client user’s name and the name of the parent domain.

An inter-realm TGT

A TGT encrypted with an inter-realm trust key derived from the ROOT$ trust account password (instead of krbtgt’s secret key). By default, the RC4 trust key is used. As a regular TGT, this TGT contains a TGS session key, but for the TGS Exchange with the parent domain. The PAC of this TGT is a copy of the PAC from the TGT sent by the client user in the TGS-REQ.

Ticket information

The information indicates that the response is a referral to the TGS of the parent domain. The ticket information is encrypted with the TGS session key retrieved by the TGS from the TGT sent by the client user in the TGS-REQ.

A TGS session key

The session key for the TGS Exchange with the parent domain. It is encrypted with the TGS session key retrieved by the TGS from the TGT sent by the client user in the TGS-REQ.

The PAC of the inter-realm ticket is a complete copy of the TGT PAC, as stated in the MS-KILE TGS Exchange documentation: “The KILE KDC MUST copy the populated fields from the PAC in the TGT to the newly created PAC …”. The TGS Exchange specifies also that the PAC must be populated with domain local group membership for the client user, except for inter-realm TGTs. No validation of the TGT PAC data seems to be performed.

TGS Exchange (parent KDC)

5) TGS-REQ

The client user decrypts the ticket information and realizes that the TGS-REP is a referral. The client user sends a new TGS-REQ, this time to the parent domain, with the NAME_CANONICALIZE option again. The TGS-REQ contains:

An authenticator

The authenticator contains the pre-authentication data send by the child domain TGS in the TGS-REP. The client user has encrypted the authenticator using the TGS session key also received from the child domain TGS TGS-REP.

The inter-realm TGT

The TGT provided by the child domain TGS in the TGS-REP.

6) TGS-REP

The KDC of the parent domain realizes that the TGS-REQ is a referral by the PA-SVR-REFERRAL-INFO pre-authentication type and decrypts the inter-realm TGT using its copy of the inter-realm trust key. The parent domain TGS gets access to the TGS sessions key from the inter-realm TGT and decrypts and verifies the authenticator. If the authenticator is valid, the TGS replies to the user client with a TGS-REQ containing:

An AP session key

The session key to be used between the client user and the service account. The AP session key is encrypted with the TGS session key.

A service ticket

The service ticket contains a copy of the AP session key and a copy of the user’s PAC from the inter-realm TGT. The PAC has been extended with authorization data from this domain i.e. domain local group memberships of this domain. The service ticket is encrypted using the secret key of the service account.

When the parent KDC creates a service ticket the PAC is again copied, but this time the PAC is populated with domain local groups. This updates some of the PAC attributes:

UserFlags: 544

In addition to flag ‘D’, UserFlags now has flag ‘H’ set which “Indicates that the ResourceGroupIds field is populated.”

ResourceGroupDomainSid: SID of parent domain

ResourceGroupIds: List of group RIDs

The list contains the RIDs of domain local groups of the parent domain of which the client user is a member. The list contains only the RIDs and not the SIDs, as all the groups begin with domain SID which is in the ResourceGroupDomainSid attribute. Global groups of the parent domain are neither in this attribute nor ExtraSids as global groups cannot contain members of other domains

ResourceGroupCount: Number of RIDs in ResourceGroupIds

From the MS documentation, it seems like entries present in ResourceGroupIds of the inter-realm TGT PAC are copied to the service ticket PAC, but our tests with forged tickets showed that our entries in ResourceGroupIds of the inter-realm TGT were removed from the PAC by the parent domain TGS and not present in the service ticket. However, all SIDs in the ExtraSids remain.

If the service account has the Resource-SID-compression-disabled flag set, the domain local group SIDs are instead added to ExtraSids.

We have observed that builtin local groups are never added to the PAC, which must mean the service account checks if the client user is a member of those groups manually. This makes sense, as these groups exist locally on Windows computers.

AP Exchange

7) AS-REQ

The client user uses the TGS-REP data to initiate an AP Exchange like the AP Exchange of a normal intra-domain Kerberos authentication, where the service account gives access based on the PAC of the service ticket.

The service account creates an ImpersonationAccessToken and populates it with the SIDs of the PAC attributes in the service ticket, and determines which access the client user has. Optional PAC validation gives the option to send a checksum of the PAC from the service account to the parent KDC to make sure it is not a forged service ticket but is not performed by default. This validation is also limited, as it will not catch if the TGT or the inter-realm TGT was forged, only forged service tickets.

Part 1 conclusion

Part 1 has explained how Kerberos authentication works, with a special focus on authentication from a child domain to a parent domain. The most important information from this blogpost, in respect to the SID filtering series, is that the SID history is added to the ExtraSids attribute of the very first PAC in the TGT, then copied to the inter-realm TGT, and then copied again to the service ticket. This all happens without validation of the SID throughout the process which means that it can be abused. This abuse will be explored in part 2: Known AD attacks - from child to parent.