This is part four of a seven part series. Check out part 1 Kerberos authentication explained for links to the others.

As demonstrated in part three (SID filtering explained), the Enterprise Domain Controllers SID, TDO SIDs, and NeverFilter SIDs were exempted from domain trust SID filtering. This blog post aims to identify rights granted to any exceptions, which can result in attacks from a child to a parent domain, thereby bypassing SID filtering as a security boundary. Two attacks, which we believe are novel, will be described: Keys container trust attack and DNS trust attack, for each we provide possible mitigations and detections, but as the conclusion says: we deem our suggested mitigations lowers the risk by such a small amount that the risk of mitigations breaking functionality is not justified. Additionally, we will describe an attack unrelated to the SID filtering exceptions: GPO on site attack.

Content

Rights granted to SID filtering exceptions

Enterprise Domain Controllers – Keys container trust attack

Enterprise Domain Controllers - DNS trust attack

Demonstration of arbitrary DNS record modification

Other Enterprise Domain Controllers rights

GPO on site attack

Why GPO on site attack works

Part 4 conclusion

Rights granted to SID filtering exceptions

The table below contains SIDs allowed to pass the domain trust SID filtering (TDOs excluded).

We found documentation on the above SIDs from the following Microsoft resources:

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/secauthz/well-known-sids

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/openspecs/windows_protocols/ms-dtyp/81d92bba-d22b-4a8c-908a-554ab29148ab

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/security/identity-protection/access-control/security-identifiers#well-known-sids

https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/topic/0fdcaf87-ee5e-8929-e54c-65e04235a634

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/openspecs/windows_protocols/ms-pac/55fc19f2-55ba-4251-8a6a-103dd7c66280

Auditing rights of the SIDs was done on the following in a parent domain:

Memberships of local and AD groups

User Rights Assignment of Domain Controllers

‘defaultSecurityDescriptor’ attribute of ‘classSchema’ objects in the AD Schema

DACL set directly (not by inheritance) on all AD objects in all naming contexts with the tool Get-ADObjectACL.ps1

DACL of all registry keys

DACL of default network shares

The audited domain was ‘root.local’ which had a child-domain ‘child.root.local’ in bi-directional trust, both domains had no additional configurations made other than the default.

We found a few interesting rights, the one principal that stood out most was Enterprise Domain Controllers (EDC), below are our findings split into two attack types:

Enterprise Domain Controllers – Keys container trust attack

Enterprise Domain Controllers – DNS trust attack

Enterprise Domain Controllers – Keys container trust attack

The key container trust attack abuses the rights granted to EDC on the Keys container as seen below:

In a default AD, the Keys container is empty. We searched through multiple large production AD environments and found no objects in, or logs relating to (365 days retention), the container.

According to Michael Grafnetter (@MGrafnetter) “the purpose of the Keys container was to store msDS-KeyCredential objects (NGC, FIDO, and STK keys). This container and class were later made obsolete and replaced by the msds-KeyCredentialLink user/computer/device attribute.”, this subject was originally researched by Ryan Ries (@JosephRyanRies).

Researching the history of these objects we found that:

The Keys container was added in Windows Server 2016.

The msDS-KeyCredential class was added to schema version 74.

The msDS-KeyCredentialLink attribute was added to schema version 80.

The msds-KeyCredentialLink attribute is also described in a BH19 talk ‘Exploiting Windows Hello for Business‘ by Michael Grafnetter and relates to:

Next-Gen Credential (NGC) – Credentials stored on TPM

Fast IDentity Online Key (FIDO) – Keys for e.g. YubiKey

Session Transport Key (STK) – Computer authentication keys

File Encryption Key (FEK, undocumented)

BitLocker Recovery Key (BitLockerRecovery, undocumented)

PIN Reset Key (AdminKey, undocumented)

This identified GenericAll (Full Control) ACE for EDC on Keys may once have allowed for EDC to compromise these keys, but in the current AD version we deem it to be not possible. However, EDC will be granted GenericAll via inheritance on any object stored in the Keys container - this allows a child domain to compromise objects stored in the parent domain’s Key container (storing objects therein may happen by accident).

Mitigations to this attack, in order of least to most risky, may be:

Move any objects out from the Keys container

Disable inheritance on the GenericAll EDC right on the Keys container

Remove the GenericAll EDC right on the Keys container

Delete the Keys container

We deem mitigations comes with a low risk of breaking stuff.

Detection of this attack may be to enable auditing on the Keys container and monitor for any creations or changes to objects within. Relevant auditing is not enabled by default on the container.

Enterprise Domain Controllers - DNS trust attack

The DNS trust attack abuses the rights granted to EDC on various DNS containers.

DNS records can be stored under one of these three distinct locations in AD, found in O’reilly’s Active Directory, 5th edition:

DomainDnsZones partition (CN=MicrosoftDNS,DC=DomainDnsZones,DC=root,DC=local)

Replicated to DCs in the domain that are also DNS servers.

ForestDnsZones partition (CN=MicrosoftDNS,DC=ForestDnsZones,DC=root,DC=local)

Replicated to DCs in the forest that are also DNS servers.

Domain partition (CN=MicrosoftDNS,CN=System,DC=root,DC=local)

Replicated to all legacy DCs in the domain. This was the only storage method available under Windows 2000.

Below we list EDC rights on only DomainDnsZones containers, but the same rights are found in the other two locations:

We found these rights may allow for two attack types:

Creation, deletion, and modification of arbitrary DNS records in any of the database locations of a parent domain. This may result in DoS or MiTM attacks.

Sub-attack 1: Modification of static DNS records created by an organization. A demonstration can be found below.

Sub-attack 2: Modification of the Active Directory DNS-Based Discovery (or DNS-SD) records, such as LDAP at “DC=_ldap._tcp.dc,DC=_msdcs.root.local,CN=MicrosoftDNS,DC=ForestDnsZones,DC=root,DC=local” which clients query to locate Domain Controllers when they join the network or during logon . Active Directory DNS-Based Discovery records also include Global Catalogue and Kerberos. This may result in DoS or MiTM attacks.

Sub-attack 3: Modification of Root Hints/Root DNS servers via the container “DC=RootDNSServers,CN=MicrosoftDNS,DC=DomainDnsZones,DC=root,DC=local”. This may result in DoS or MiTM attacks.

The typical DnsAdmins group abuse technique by setting ServerLevelPluginDLL may be possible. However, when performing the technique from a child domain an error is returned: “ERROR_ACCESS_DENIED 5 0x5”. We did not research this further. If successful, this may result in code execution on a parent domain Domain Controller.

Mitigations to this attack may be to remove the create, delete, and write rights on the objects. We do not know the risk of breaking stuff, but we deem it to be medium to high.

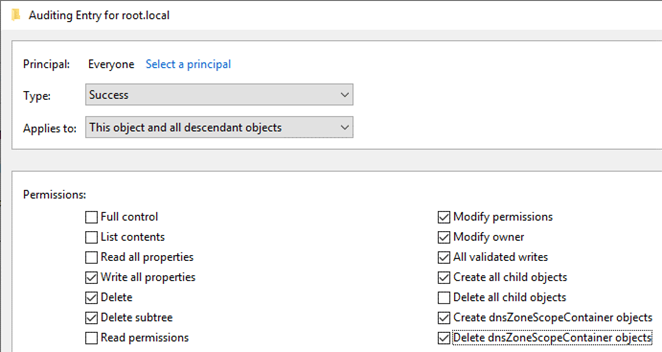

Detection of this attack can be to enable auditing on the objects and monitor for any changes to the objects and their child-objects by a child Domain Controller. It is important to ensure auditing upon both DACL and SACL changes, as EDC can modify both. Relevant auditing is not enabled by default on any of the objects.

To demonstrate detection, the following SACL is added to “DC=root.local,CN=MicrosoftDNS,DC=DomainDnsZones,DC=root,DC=local”:

A modification by an EDC in the child domain (as demonstrated later) thereafter generates an event:

Demonstration of arbitrary DNS record modification

An A-record for ‘intranet.root.local’ is created on ROOT-DC-01.root.local:

With SYSTEM privileges on CHILD-DC-01.child.root.local the DNS record is queried, changed, and then queried again to confirm the change:

Copy-pasteable commands:

PS C:\> Resolve-DnsName -Name intranet.root.local -Server root-dc-01.root.local | select -ExpandProperty IPAddress

192.168.229.50

PS C:\> $Old = Get-DnsServerResourceRecord -ComputerName root-dc-01.root.local -ZoneName root.local -Name intranet

PS C:\> $New = $Old.Clone()

PS C:\> $New.RecordData.IPv4Address = [System.Net.IPAddress]::parse('10.10.10.50')

PS C:\> Set-DnsServerResourceRecord -NewInputObject $New -OldInputObject $Old -ComputerName root-dc-01.root.local -ZoneName root.local

PS C:\> Resolve-DnsName -Name intranet.root.local -Server root-dc-01.root.local | select -ExpandProperty IPAddress

10.10.10.50Back at ROOT-DC-01.root.local we also confirm the change:

Other Enterprise Domain Controllers rights

GPOs: EDC are granted read rights on new GPOs (and default policies) in the parent domain, enabling techniques such as discovery of misconfigurations and account passwords pushed via Group Policy Preferences. Authenticated Users are granted the right too, meaning the EDC right is only relevant for GPOs where the read right of Authenticated Users is removed. The right is set by the ‘defaultSecurityDescriptor’ attribute of the schema’s ‘Group-Policy-Container’ object.

User Rights Assignment: EDC are granted User Rights Assignment (URA) ‘Allow log on locally’ and ‘Access this computer from the network’ on Domain Controllers in the parent domain via the GPO ‘Default Domain Controllers Policy’. While these rights might sound sufficient for remote login, they are not. You need the RDP privilege (SeRemoteInteractiveLogonRight) or membership of a privileged group like Administrators. If that was not the case, members of Domain Users would be able to remote into any domain-joined Windows machine in a default configured AD, which would be a true nightmare.

GPO on site attack

While researching SID filtering bypasses, we got asked if we had tested if the ‘GPO on site’ attack worked with SID filtering enabled. We were not familiar with this attack method (why it is not included in part 2 – known attacks). The person said that SYSTEM on a child DC was able to link GPOs to AD replication sites, even sites where parent DCs are located.

First, we check which replication site the root DC is in:

Then, starting PowerShell as SYSTEM on the child DC, and linking it a to test GPO to the default site:

On the root DC we confirm that the GPO is applied:

A GPO can contain many different settings which enable remote code execution on the root DC. One example a GPO creating a scheduled task which executes a PowerShell reverse shell in SYSTEM context. A simpler attack would be to add a compromised user to ROOT\Administrators.

The GPO on site attack works with SID filtering enabled, making SID filtering on domain trust an ineffectual security boundary.

The person claims to have found this attack method by themselves years ago. We have not been able to find any online resource describing this attack method.

Why GPO on site attack works

The only entities with the necessary rights to link a GPO to the replication site are ‘NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM’, ‘ROOT\Enterprise Admins’, and ‘ROOT\Domain Admins’:

When we run as SYSTEM on a child DC, we do have the ‘NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM’ SID in our access token, but it can only be used on the local system, as this is the context of where we are SYSTEM, and not on remote systems like the parent DC. This is also why we must specify the ‘server’ argument of child.root.local when linking the GPO. Without the argument we get access denied, as it will by default send the command to the root domain, as the site is located under ‘CN=Configuration,DC=root,DC=local’ and not ‘DC=child,DC=root,DC=local’.

So, if the replication site object is located under the root domain, why is it writable on a child DC? It turns out the entire Configuration naming context (NC) (CN=Configuration,DC=root,DC=local) is stored on all DCs a forest, again from O’reilly’s Active Directory book: “The Configuration NC is the primary repository for configuration information for a forest and is replicated to every domain controller in the forest. Additionally, every writable domain controller in the forest holds a writable copy of the Configuration NC.”

This means a child DC can read and write (if not a read-only DC) anything under the Configuration NC for the forest by querying its local replica.

Conclusion

In this post, we audited default DACLs in an AD domain to identify possible abuses of SID filtering exceptions. Two possible intra-forest trust attacks were described – Keys Container trust attack and DNS trust attack – the latter also demonstrated with one of its two described sub-attacks. Additionally, other rights were also mentioned about GPOs and User Rights Assignment.

We demonstrated with the GPO on site attack that SID filtering on domain trusts does not prevent the attack. At last, we explained how all regular DCs (not read-only) in a domain can read and write anything under the Configuration NC.

The existence of these attacks makes SID filtering an ineffective security boundary between domains, and therefore we deem our suggested mitigations lowers the risk by such a small amount that the risk of mitigations breaking functionality is not justified.

This answers the original question of our series “can we use SID filtering to make the domain a security boundary?”, but this is not the last blog post. The next two blog posts demonstrate two different child-parent attacks which are also not prevented by SID filtering but made possible of the described Configuration NC functionality. Our last blog post no. 7 will describe yet another attack we discovered, but it works across any type of trust, even forest trust. So, stay tuned!